SUSTAIN

Work to engage, understand, plan, and implement climate change adaptation requires energy and resources, now and into the future. You must continuously make the business case for this work, monitor and assess conditions, sustain connections with partners, and learn how new information fits into what is already known. This work also requires an abundance of patience and perseverance.

Leading practices in the SUSTAIN action area illustrate ways WUCA members have initiated climate adaptation work and kept it going.

In the SUSTAIN action area, leading practices include:

- Make the business case for climate adaptation (also in ENGAGE)

- Leverage existing funding mechanisms (also in PLAN)

- Monitor and evaluate current conditions

- Approach climate change adaptation through mainstreaming

- Avoid new climate science whiplash

- Keep moving forward, even if it feels slow

- Value climate adaptation as more than a plan

- Establish a community of practice to integrate climate change adaptation

- Build and maintain in-house capacity (also in PLAN)

- Seek out and support climate champions throughout your utility (also in ENGAGE)

Make the business case for climate adaptation

Improving resiliency takes time and resources but can also save time and resources. Transparency about financial elements, including tradeoffs in costs and other triple-bottom-line benefits — social, environmental, and financial — can motivate action and demonstrate how adaptation investments can save money in the long run. This helps engage people from the beginning and sustain the effort.

This practice is both a SUSTAIN and ENGAGE climate adaptation action.

Study highlights costs and benefits of climate adaptation.

SOURCE: NYC DEP

Example: Flood protection benefits in New York City

In 2011, New York City (NYC) Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) initiated an internally funded pilot study of climate change impacts on its drainage system and wastewater treatment, looking at potential risks based on projected temperature, precipitation, and sea level rise. When Superstorm Sandy hit New York in 2012, DEP expanded the assessment to all vulnerable treatment facilities and pumping stations to consider risks from future storm surge events with sea level rise.

The result of the study is a portfolio of adaptive approaches described in the 2013 NYC Wastewater Resiliency Plan, including elevating and flood-proofing critical equipment. The plan showed that by investing in flood protection, NYC could avoid over $2 billion in estimated damages to waterfront facilities from 50+ years of flooding.

This business case was helpful in securing over $160 million in federal funding for retrofits at DEP wastewater treatment facilities and pumping stations.

Example: A drought-proof water supply in San Diego

San Diego County Water Authority (SDCWA) updated their Regional Water Facilities Master Plan in 2013 to serve as a roadmap for major capital improvements needed to ensure the region's supply reliability under changing demand and supply conditions. The plan identified a suite of capital facilities to increase supply reliability (motivated by core responsibilities, as highlighted here: Example: Supply resiliency).

This new, drought-proof supply reduces the region's dependence on water from the Colorado River and the Bay-Delta that is vulnerable to droughts, natural disasters, and regulatory restrictions. The CDP has a capacity of 56,000 acre-feet per year, and not only improves long-term water supply reliability for the San Diego region, but also helps all of California by reducing pressure on the state's strained water resources. As such, even though water from the Carlsbad Desalination plant is more expensive than the region’s traditional imported water sources, it has significant advantages in being drought-proof and locally controlled. Learn more about SDCWA's infrastructure at: Example: A diverse water supply portfolio.

Additional resources

Leverage existing funding mechanisms

Work to engage, understand, plan, and implement climate change adaptation requires financial resources. Funding is also needed to sustain efforts. State or federal government funding possibilities may exist; they just need to be discovered and leveraged, sometimes creatively.

Example: State and federal loans

Innovation is essential when thinking about ways that funding from established programs could be used to implement climate-related projects. Austin Water (AW) received funding from state and federal loan programs for green projects. Through the Texas SWIFT loan program, AW expanded its reclaimed water infrastructure ($65 million) and began initiation of an advanced metering infrastructure program ($81 million).

In 2010, AW received a zero-interest, 30-year loan through the federal Clean Water State Revolving Fund green reserve program. This allowed AW to reduce methane leakage and expand the biosolids compost facilities as well as get a biogas generator that produces most of the electricity used at the Hornsby Bend biosolids plant ($32 million). These loan programs helped AW reduce the debt for these projects. With SWIFT, AW received a 35 percent interest rate discount for a 20-year loan term, saving the utility $10 to $17 million for every $100 million loan.

While the zero interest was unique to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act federal stimulus, the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds are still available for utilities across the country with significant interest rate discounts. Green reserve components can result in a portion of principal forgiveness or further interest rate discounts depending on the individual state. While these programs were focused on greenhouse gas mitigation and not specifically identified as climate adaptation projects, they proved to be cost-effective tools in helping AW make infrastructure investments to prepare for a changing climate.

Read more at:

- Texas Water Development Board State Water Implementation Fund for Texas (SWIFT)

- Texas Water Development Board Clean Water State Revolving Fund Loan Program

- Clean Water State Revolving Fund

Photo: Hornsby Bend Biosolids Management Plant

SOURCE: Ash Bledsoe

Additional resources on funding mechanisms

- EPA's Climate Change Adaptation Resource Center

- EPA's Water Infrastructure and Resiliency Finance Center hosted a webinar in 2016 on how states and communities use state revolving fund, FEMA, and other financing approaches to recover from a disaster, at which utility and state speakers shared their tips and examples. Watch it here.

- EPA's Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loans

- EPA's Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds

- FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities

Monitor and evaluate current conditions

Knowing current climate conditions and tracking how they change is important. Monitoring programs can allow for incremental adaptations that employ resources as needed, based on if and when important thresholds are exceeded. Then, pairing monitoring with evaluation can help you understand whether your implemented processes and actions actually achieve targets and goals.

UNDERSTAND: Recognize the value of long-term monitoring outlines what has (or should) be monitored, and examples of sustaining a monitoring effort are shared below.

Example: Sea level rise monitoring

Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) has over 115 years of tide level data from a NOAA tide station. PWD analyzes this data, carefully monitoring tide levels to understand how quickly sea levels are rising and whether sea level rise is speeding up.

Understanding trends over time is very tricky. Based on past data, PWD knows there has been significant inter-annual, annual, decadal, and multi-decadal natural variation. The long tide record helps to understand how near-term sea level rise projections align with recent decadal trends.

For more information about how PWD works with sea level data, see Example: Past sea levels inform future planning.

Additional resources

Federal agencies have long-term monitoring networks that may provide valuable information.

- USGS: US Geological Survey provides publicly available data and tools for many parameters such as streamflow at over 70,000 sites

- NOAA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration hosts many climate data sets:

- State or local offices could also provide valuable insight and access to data.

- State Climatologist – each state has its own assigned climatologist.

Working with local academics could help uncover what measures already exist that could help inform adaptation, see UNDERSTAND: Foster sustained relationships with the climate science community.

Understanding the natural system over time and having long data sets available to analyze and look for trends has been vital to Philadelphia Water Department's climate adaptation efforts.

Approach climate adaptation through mainstreaming

Creating utility-wide climate resilience can be achieved by examining climate change impacts and implementing adaptation solutions throughout organizational activities. Coined "mainstreaming," this approach allows utility subject matter experts to work with their climate leads or champions to co-produce relevant and timely adaptation solutions. By understanding risks and identifying solutions with staff, mainstreaming builds the adaptive capacity needed to ensure water systems, operations, resources, and investments are diversified, flexible, redundant, and resilient.

Example: Mainstreaming Risks and Opportunities

In the summer of 2020, Denver Water piloted a new Water Research Foundation risks and opportunities framework for mapping climate exposure and climate information needs to water utility business functions (WRF #4729). Denver Water used this framework to conduct a tabletop exercise with over 25 staff member participants from four utility business functions: finance, water treatment, water distribution/hydraulics, and watershed management.

Before the tabletop exercise commenced, Denver Water's climate team created a tabletop steering committee with one representative from each business function and presented a "Climate 101" education session to all groups participating. This co-production planning approach, together with the climate education sessions, helped ensure the stage was properly set before the exercise began.

The exercise, led by a consultant team with expertise in tabletop exercises, allowed the collective group of subject matter experts to reflect on how climate change has already impacted the utility. It also helped them discuss how two different future climate change scenarios could impact each business function and brainstorm potential adaptation solutions that can be implemented to mitigate climate change risks and capitalize on opportunities.

Staff members remained deeply engaged throughout the entire process and were excited to learn more about climate change, as well as to share their ideas for solutions (having a session focused only on brainstorming solutions proved to be an extremely valuable part of the exercise and provided many subject-specific solutions that the climate team wouldn't have otherwise been exposed to). Staff members were also pleased to have an opportunity to spend an extended amount of time learning from, and strategizing with, colleagues from other departments with whom they do not regularly interact.

Driven by stakeholder input from the four business functions represented, the process allowed for the solutions to be generated directly by the subject matter experts who will be most directly involved in their implementation. And importantly, the exercise provided a formal mechanism for integrating climate change thinking and planning throughout the utility.

More on the Water Resource Foundation framework (WRF #4729)

More on using a new Risk and Opportunities Framework with four utility business functions: Finance, Watersheds, Water Treatment, and Water Distribution.

More ways utilities are considering mainstreaming:

- Southern Nevada Water Authority's enterprise risk management highlighted mainstreaming climate change considerations across the organization as part of staff's daily work activities to mitigate risks, see Example: Enterprise Risk Management.

- Portland Water Bureau's strategic plan includes climate change adaptation—the plan identifies strategies for addressing climate impacts to multiple parts of the organization, see Example: Strategic Planning.

Avoid new climate science whiplash

New science is not necessarily better or more predictive. Climate science moves forward in an iterative fashion. Usually, through these iterations, a common understanding develops—though consensus and synthesis take time and don’t often make headlines. Put another way, flashy new findings and scientific debate may cause whiplash, whereas scientific assessments synthesize and report new knowledge in a more deliberative way.

Example: New global climate models

In 2018 the Portland Water Bureau (PWB) engaged in research using Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) Phase 6 outputs to study projected changes to Portland's water supply. From 2013 to 2018 PWB had used CMIP5 models, which were thoroughly vetted and assessed nationally and regionally in the Pacific Northwest.

CMIP6 models were only recently and gradually being released when PWB's newer research took place; at the time, there was no synthesis or model evaluation of these model outputs, and no assessment on model skill or comparison of projections to CMIP5. Due to lack of scientific synthesis and the context synthesis provides, PWB faced challenges interpreting the results using a subset of the CMIP6 models and grappled with how much confidence to place in the CMIP6 model projections and outputs.

A valuable lesson learned from this process was that newly released climate science and model projections may not be immediately usable or "actionable" for water utilities and other practitioners, which can limit the usefulness of the data for decision-making purposes, at least until an assessment of the new science occurs. However, using the newer climate models allowed the utility to perform a "stress test" of more extreme greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, which can help inform worst-case scenario planning.

Example: Sea level rise science

San Francisco's efforts to estimate projected sea level rise (SLR) illustrate two important features in working with science:

- Digging into scientific documents can reveal valuable information for adaptation planning

- Building and leveraging relationships with scientists who can explain the science helps advance the adaptation agenda

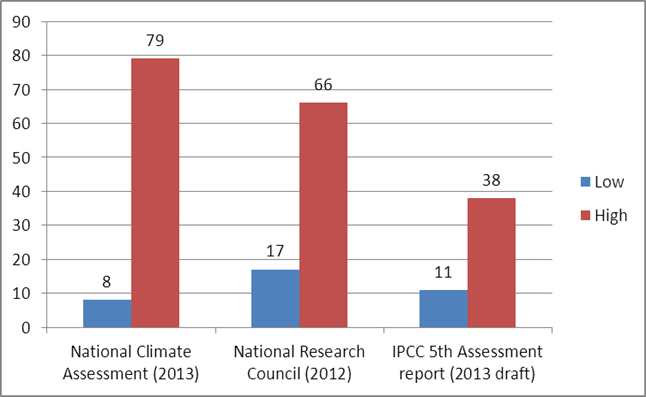

In 2013, when the City began developing its first SLR guidance (see Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) 5th Assessment Report, 3rd National Climate Assessment (NCA), and a 2012 National Research Council (NRC) report had recently been released. These authoritative sources showed widely divergent SLR projections out to 2100, particularly the "unlikely but possible" or so-called "high-end" projections based on best available science, as shown below.

Each report made reasonable assumptions that appeared, to a layperson, to lead to very different adaptation outcomes. Through extensive interviews with the three reports’ authors (made possible by leveraging WUCA relationships), City staff discovered that while each report used a different rationale for the range of projections, the reports more or less agreed with one another. While the NCA report included a high-end number at the upper limit of projected SLR supported by the science at the time, the NRC, chose 66 inches, a number more widely supported by multiple lines of evidence. Ultimately, San Francisco staff determined that 66 inches was the best high-end projection for their planning.

Because planning only for extreme high and low projections limits adaptation options, San Francisco sought a midrange estimate to comply with state guidance. After establishing the NRC report as best available science, additional author interviews uncovered a "projection" figure of 36 inches (buried in several tables with minimal explanatory language) that represented the NRC's best estimate of the median sea level rise projection. This projection was essentially identical to the IPCC's 38-inch projection. Therefore, in its planning guidance, City planners adopted 36 inches and 66 inches as the median and high-end projections, respectively.

Related leading practices on sea level rise

- Example: Sea level rise science in practice under UNDERSTAND: Be a savvy consumer; recognize values and limits of climate science in practice

- Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise under PLAN: Leverage the power of well-placed climate change screening questions

- Example: Sea level rise projections under PLAN: Plan for a range of futures, not a single future

Reports discussed above

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group 1 Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for Policymakers.

- National Research Council report: Sea Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future. National Research Council, 2012

- National Climate Assessment report: Parris, A., et al. Global Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States National Climate Assessment, December 6, 2012, produced for NOAA, USGS, SERDP and USACE

Websites and reports released since 2013

- Sea level rise explainer

- IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate

- Sea level rise assessment for the state of Washington (other regions, states, or cities might have similar resources)

The range of sea level rise projections (in inches) for 2100 reported by three different sea level rise assessments available in 2013.

SOURCE: San Francisco Public Utility Commission

Keep moving forward, even if it feels slow

Change is rarely easy, especially when building institutional capacity to adapt to climate change; it can feel slow. It is important to keep at it and move forward carefully. In some situations, being too forceful or alarmist could unintentionally create more barriers.

Example: The importance of groundwork

Indirectly and slowly adapting to climate change is better than no adaptation efforts at all. Sometimes preliminary steps to inform the need for more direct action on climate adaptation is necessary. In the case of the Central Arizona Project (CAP), several analytical and research efforts were pursued to understand the impact of climate change on CAP and its resources prior to committing to a comprehensive organizational Climate Adaptation Plan.

These efforts included modeling Colorado River water supply using climate-downscaled hydrology, attempting to improve near-term Colorado River streamflow predictions using synoptic storm patterns and sea surface temperatures, and exploring dynamic downscaling data to improve GCM simulations of Colorado River Basin precipitation. All of these studies helped CAP set the groundwork for further and more far-reaching climate adaptation activities.

View the synoptic storm patterns report conducted for CAP by the Desert Research Institute

Value climate adaptation as more than a plan

While the focus is often on the resulting plan, it is the process of planning that is most important. Creating and reinforcing the connections and processes required to adapt to climate change builds valuable institutional capacity that will serve the utility even if the plan itself is not used.

Example: Scenario planning as a process

Portland Water Bureau's (PWB) 2001 Infrastructure Master Plan adopted a fairly common, traditional planning approach: deterministically predicting and assuming future demands and the exact supply gap that would result from anticipated higher future demand and climate change. These predictions were already outdated not long after the plan was developed because demand decreased due to higher customer water efficiency. From this experience, the utility learned that planning for one single future is neither a robust nor an adaptive way to deal with future uncertainty.

Through WUCA, the Portland Water Bureau learned about approaches better able to accommodate future uncertainty and decided to adopt a scenario planning approach for its forthcoming long-range Supply System Master Plan. This new plan applied an adaptive planning "roadmap" for several future uncertainties: climate change, population growth, water demand trends, availability of utility funds, and other environmental and socio-economic factors.

The planning process was transformative because it required staff to consider more than one future outcome and which investments and strategies would work best under different conditions. This in itself is a groundbreaking outcome. The hope is that an adaptive roadmap will foster an iterative supply system planning process within the utility, requiring regular reassessments and monitoring of situational and changing conditions, and that this adaptive approach could be applied to other aspects of Portland Water's planning processes.

The utility is now engaged in this adaptive planning process, which entails an annual review of monitoring indicators and situational assessment, a five-year more detailed review of key trends, and updated modeling of water supply and demand forecast for the next 30+ years.

The Portland Water Bureau's Supply System Master Plan and roadmap will summarize the adaptive planning approach (forthcoming 2021).

More scenario planning examples and resources can be found at: PLAN: Employ decision-making science and deep uncertainty concepts.

Climate adaptation planning can influence an organization's broader approach to future planning.

Establish a community of practice to integrate climate change adaptation

Climate change adaptation and mitigation are organization-wide endeavors that impact planning, policy, operations, and investments. Because this work is cross-cutting, it benefits from a clear agenda and shared, collaborative leadership. Establishing a community of practice, within an organization or through shared impact focus areas across organizations, can provide a supportive forum in which to investigate ideas, define focus, share knowledge, and communally advance and celebrate progress. Activities can be initiated by a single person or group, or a collection of people from different groups—ideally with support distributed so responsibilities can be shared.

Below are some examples of how a community of practice might come together.

Example: A community of climate champions in Seattle

To bring greater clarity and cohesion to its climate work, Seattle Public Utilities established a community of practice that brings together climate practitioners, utility (and outside) subject matter experts, and climate enthusiasts from across the organization.

The community of practice convenes quarterly to share broadly about climate-related information, impacts, initiatives, concerns, and innovations and to develop a shared climate agenda to structure and align the utilities' climate work and commitments in all areas.

Community of practice members tour the utility's transfer facilities.

SOURCE: Seattle Public Utilities

Example: Sustaining climate champions through a climate adaptation committee in Denver

Climate champions throughout an organization can allow for more widespread knowledge distribution and help foster broad and successful adaptation. Effective change requires repetition of understandable messages and many voices relaying consistent messaging. An important goal at Denver Water is to empower employees to bring climate thinking into their areas of work. One way to achieve this is create a climate adaptation committee to educate, encourage, and support champions throughout the organization.

It is important to strategically identify areas within an organization where a champion will help meet climate adaptation goals and to utilize people who are already trusted sources within their groups as well as individuals who are interested and passionate about climate adaptation.

Meeting with the committee of champions regularly (quarterly, for example) keeps champions informed of new science and recent internal activities, as well as interested and engaged. Meetings should add value to all attendees and enhance organization-wide momentum. Regular meetings will also help develop critical two-way lines of communication necessary to support champions' efforts to bring climate adaptation into their area of expertise and help keep these important advocates motivated.

Example: Learning together

In 2017, WUCA developed and hosted its first technical climate science and adaptation training in collaboration with EPA's Creating Resilient Water Utilities (CRWU) program and other partners. "Building Resilience to a Changing Climate: A Technical Training in Water Sector Utility Decision Support" focuses on the practical use of climate science [UNDERSTAND, example: Learning about climate change science] in adaptation planning, decision making under conditions of uncertainty [PLAN, example: Planning amid uncertainty training], generating buy-in for resilience investments, and addressing communications barriers [ENGAGE, example: Communication training].

Each training is hosted in a different region by a WUCA member and helps to create and inform a regional climate adaptation community, with case studies that highlight lessons learned [PLAN, example: WUCA Climate Resilience Training peer learning]. Following each training, participants are encouraged to maintain engagement, continue learning, and begin work together to address the challenges of a changing climate [SUSTAIN: Establish a community of practice to integrate climate change].

WUCA's collaborative has successfully planned and held two trainings per year (excluding 2020) following the initial development and kickoff in Boulder, Colorado. While in-person events in 2020 were postponed due to COVID, WUCA worked with the EPA and NOAA to begin transitioning training materials to a virtual platform hosted on NOAA's climate toolkit website to allow for broader access to the training. When complete, WUCA's virtual training will lay the foundation for a future water utility climate adaptation certification program.

SOURCE: Tampa Bay

Example: Regional communities of champions

Fostering engagement across organizations within a region has also been helpful. In some places, these groups already exist, such as the Florida Water and Climate Alliance (described in Example: A regional alliance) and the Front Range Climate Change Group (described in Example: A simple vulnerability assessment).

Increasingly, more organizations are focused on supporting networking between small to mid-size communities. Examples include the American Society of Adaptation Professionals, NOAA Regional Climate Integrated Assessment program, Mountain West Climate Services Partnership, and Western Adaptation Alliance, and the list continues to grow.

Additional resources

For more information about how to build successful communities of practice, see the plethora of articles and books online and stay open to experimentation and improvements.

For more examples of ways utilities have fostered climate champions, see ENGAGE|SUSTAIN: Seek out and support climate champions throughout your utility.

- American Society of Adaptation Professionals

- NOAA Regional Climate Integrated Assessment program

- Mountain West Climate Services Partnership

- Western Adaptation Alliance: A network of sustainability focused community leaders in the Mountain West that meet periodically to share experiences in climate change adaptation, for more information email climateservices@agci.org.

Build and maintain in-house capacity

Climate adaptation work can be done both within and outside of an organization, though action ultimately requires work within. It can be a significant undertaking, requiring hiring or redirecting staff time. It is better to not assume people can incorporate climate adaptation work into their existing responsibilities.

Examples for this practice can be found in the PLAN section.

Seek out and support climate champions throughout your utility

Progress happens more quickly with the support of motivated individuals who value and prioritize climate adaptation work, including executive-level leaders. It is therefore important to build relationships with and educate champions who can influence climate adaptation actions, then help sustain and strengthen those efforts. Having champions across an organization (in planning, engineering, finance, public relations, and other roles) can contribute diverse expertise and resources and help provide institutional memory as individuals' roles change.

Examples for this practice can be found in the ENGAGE section.