As the atmosphere warms due to climate change, there is a direct impact on the hydrologic cycle, thus creating unique challenges for the water sector. The effects of sea level rise and other associated coastal changes (e.g., storm surge, erosion, and flooding) have already had a wide range of impacts on coastal communities, and climate change will only exacerbate these challenges in the future. The hardships brought on by climate change are forcing a paradigm shift for decision-making in the water sector as practitioners seek to implement options to avoid, minimize, mitigate, and/or recover from the effects of these climate-driven impacts—an effort collectively known as adaptation.

This guide is intended to provide tangible, replicable practices to help water1 utility staff and water resource managers advance adaptation efforts in the face of climate change. Sea level rise adaptation is context-specific (e.g., by location, by asset, and by system), and while there is no one-size-fits-all approach to adaptation, there are principles—or leading practices—that may help water sector practitioners move towards on-the-ground implementation.

In this guide, implementation is defined as the process of making something active or effective that advances adaptation to sea level rise in a concrete way.

This implies progress beyond understanding and assessing risk to executing policies (e.g., updated design standards), projects (e.g., building a desalination plant), process changes, or programs that proactively take action to boost resilience to climate impacts in the coastal zone (e.g., capacity building).

Quick Links & Resources

- Barriers to Adaptation in the Water Sector

- References

- Appendices

- Acknowledgments

- Acronyms and Terminology

- Full Report PDF

This report is brought to you by EcoAdapt and the Water Utility Climate Alliance.

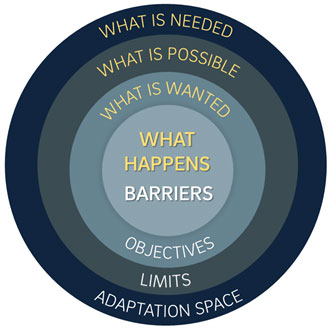

It is important to distinguish the difference between adaptation constraints or barriers and adaptation limits. Barriers include challenges or obstacles that slow or halt progress on adaptation but that can be overcome with a concerted effort. Alternatively, a limit is something that cannot, without unreasonable action or expense, be overcome (CoastAdapt 2017; Klein et al. 2014). An example of an adaptation limit would be the lack of physical space in a dense urban environment to create a nature-based solution, such as wetlands, as a coastal defense to sea level rise and storm surge. An example of an adaptation barrier is a lack of political will from organizational leaders.

There are many barriers that prevent adaptation implementation. The most frequently cited adaptation barriers include governance, financial, technical, and social/cultural barriers. These barriers, and suggested strategies to overcome them, are used to frame the content of this guide.

This guide is the outcome of a multi-year Water Utility Climate Alliance (WUCA) project designed to identify leading practices—recognizing that in this emerging dynamic field, "best practices" have yet to be established—to overcome these barriers. Tangible, real-world examples are provided when possible and help identify opportunities for the advancement of sea level rise adaptation measures.

Identifying Leading Practices

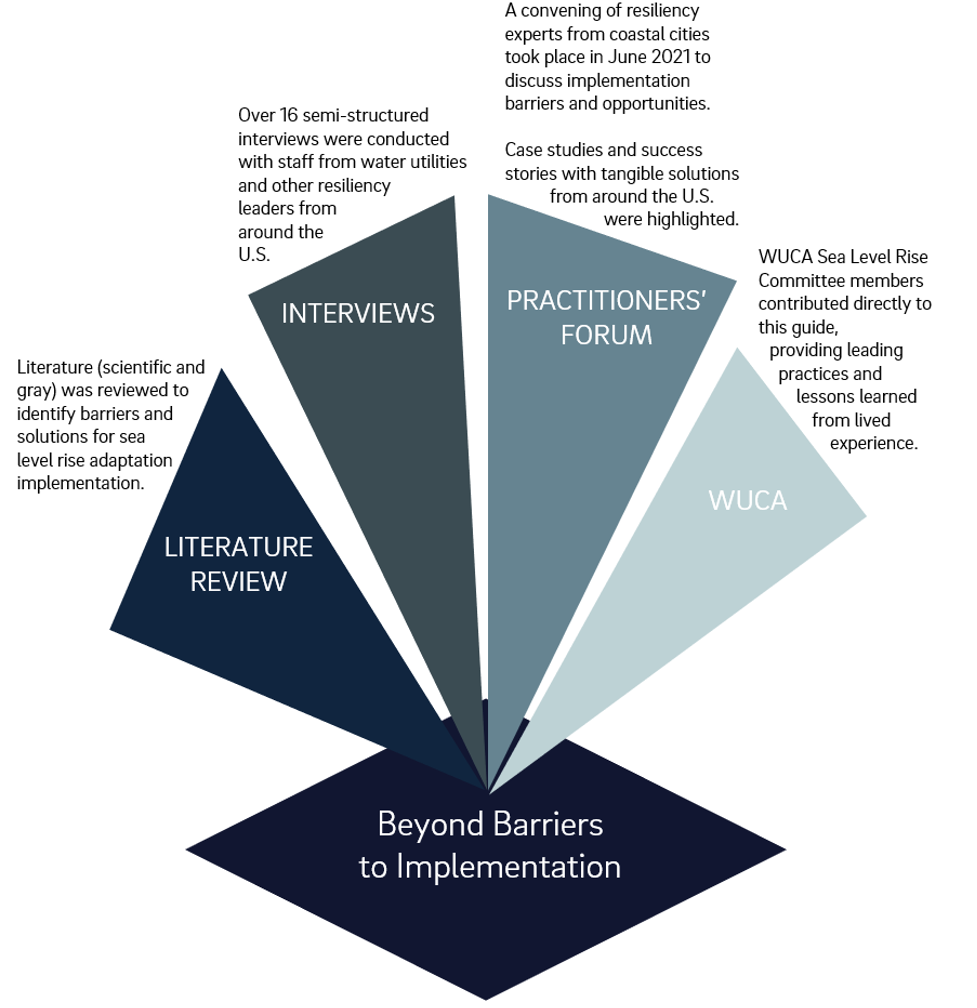

Expertise on adaptation options, common barriers to implementation, and opportunities for advancing action was solicited via a scientific and gray (e.g., white papers, agency reports and plans) literature review, semi-structured interviews, a practitioner's forum with over 60 resilience leaders from around the U.S., and from the summation of the lived experience of the following WUCA Sea Level Rise Committee members: Philadelphia Water Department, New York City Department of Environmental Protection, Tampa Bay Water, San Diego County Water Authority, San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and Seattle Public Utilities.

Leading Practices in Climate Adaptation, published in 2021 by WUCA in collaboration with the Aspen Global Change Institute, identifies a series of overarching leading practices for climate change adaptation in the water sector. The report was developed through the first-hand experience of WUCA members, and the information is organized under five action areas: Engage, Understand, Plan, Implement, and Sustain. Adaptation action areas and the associated leading practices are presented in the form of a wheel, which illustrates their inherent interconnectedness. While there may be some linearity in the process (e.g., understanding, planning, and prioritizing of adaptation options leads to implementation), engagement with these adaptation action areas can happen at any stage.

This guide builds upon the success of that body of work and uses a similar format but focuses on one climate impact, sea level rise. Resources are provided for all adaptation action areas, but this document takes a close look at the implement phase and seeks to answer the question: What barriers are preventing the water sector from advancing past the vulnerability/risk assessment phase to actually implementing projects or policies that build resilience, and how can those barriers be overcome?

How to use this Guide

Water utilities and wholesale water providers do not function in a silo, and adaptation processes—from engagement to monitoring and evaluation of implemented strategies—must be coordinated with other municipal sectors and landowners, local organizations, tribal nations, community members, regional planning bodies, regulators, and all levels of government. Acknowledging this necessary coordination, this guide was developed with input from stakeholders in multiple sectors. Likewise, many of the leading practices and tools may be applicable beyond the water sector. However, leading practices particularly relevant to this field were chosen for inclusion, and it was developed from the water sector perspective with that audience in mind. It is meant to help other water utilities and resource managers begin implementing actions to adapt to sea level rise.

This guide does:

- Provide a high-level overview of the general steps required to initiate sea level rise adaptation and includes resources and tools to support each step

- Detail the most frequent challenges encountered when reaching the point of implementation

- Suggest solutions based on leading practices for overcoming barriers, using real-life examples when possible

This guide does not:

- Provide a detailed roadmap with all the necessary steps to achieve sea level rise adaptation

- Provide a deep dive into the technical aspects of sea level rise, such as the science behind projections, working with tide level data, or risk assessment methods

- Examine every aspect of how sea level rise and related issues may potentially affect your water utility or your geographic location

- Provide a step-by-step adaptation plan and strategy for specific utility assets or system types

Guide structure

This guide is organized as follows:

- Sea Level Rise Impacts on the Water Sector – this section provides useful context for the rest of the document.

- Barriers to Adaptation in the Water Sector – this section is organized by governance, technical, financial, and social/cultural adaptation barriers. Each barrier section provides a summary of the challenges, followed by leading practices to address them. Specific leading practices are identified and supported by targeted solutions using real-world examples. While each leading practice responds to one specific barrier, there are often case studies or practices that could apply as a solution to overcome multiple barriers.

- Final Remarks – this section summarizes the key findings that emerged while developing this report.

- Appendices – this section includes an extensive appendix section with resources and tools to assist with all adaptation action areas; an adaptation pathways and application matrix; and an extensive literature review covering sea level rise adaptation and risk management strategies for the water sector.

Sea Level Rise Impacts on the Water Sector

Since 1900, global sea levels have risen between roughly 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 cm). Observed data indicate that the average rate of sea level rise increased over the twentieth century, and current projections show that the rate of these changes will continue to accelerate (Gulev et al. 2021). Currently, in the United States an estimated 133.2 million people live in coastal areas, putting them at risk of sea level rise-induced flooding, and populations continue to move closer to the coast every year (Fleming et al. 2018).

While sea level rise is a global phenomenon that is influenced by atmospheric warming and greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., melting ice and thermal expansion), the rate of rising and its consequences can vary significantly by location (Sweet et al. 2022). The local effects of sea level rise are heavily influenced by climatic factors such as weather events (e.g., storm surge), ocean circulation, and natural climatic variability (e.g., tidal fluctuations and El Niño Southern Oscillation2), as well as non-climatic factors, such as geological processes (e.g., vertical land movement, glacial isostatic adjustment3, and tectonics), and human activities that alter the coastal zone (e.g., shoreline hardening, changes to sediment input, dune removal, and dredging), which can cause flooding that reaches farther inland. Higher sea levels amplify related impacts, such as storm surge, high tides, saltwater intrusion, wetland loss, and coastal erosion, which threaten coastal ecosystems, infrastructure, and communities (Azevedo de Almeida & Mostafavi 2016; Thorne et al. 2018; Oppenheimer et al. 2019).

Sea level rise, especially in combination with other climate hazards and weather events, presents compounding challenges that will affect drinking water, stormwater, and wastewater utilities' above and below-ground infrastructure and general operating capacity. Sea level rise may contaminate drinking water sources, and flooding may cause structural damage to treatment facilities, pumping stations, water intakes, underground pipes, and other assets within a utility's system. Impacts on gravity-fed drainage systems and facility damage could lead to the release of untreated wastewater and cause basement backups or infrastructure flooding in streets. These impacts from sea level rise could also put utility staff in danger and cause a facility to be completely or partially cut off from the surrounding areas, thus preventing staff from accessing critical locations that are crucial for operations. This can lead to disruptions in critical public services, a degradation of nearby natural habitats, and a loss of trust from the public.

Direct and indirect impacts of sea level rise and coastal flooding

- Increased erosion

- Increased damage to critical water infrastructure

- Degraded water quality (increased salinity of surface, groundwater, and aquifers)

- Degradation of coastal ecosystems and disruption of services they provide (e.g.,water purification and filtration, flood protection)

- Degradation of habitat for aquatic and shoreline species

- Increased displacement of residents, communities, and businesses

- Increased risks to public health and safety

- Increased disruption of or damage to critical services (e.g., transportation, hospitals)

Adaptation and the Water Sector

Adaptation refers to efforts to avoid, minimize, and/or recover from the effects of climate change. Adaptation is an iterative process wherein decisions need to be implemented, monitored, and adjusted as needed based on practical experience as future conditions are realized; this is often referred to as adaptive risk management. Whether preparing for or responding to sea level rise or the combined effects of multiple climate change impacts, adaptation can be very context-specific (e.g., by site, by asset, by system). The best adaptation option for a utility in one coastal location may not be as effective for another utility in a different geography. In other words, there is no one-size fits all solution. Additionally, some sea level adaptation strategies may present a utility with multiple benefits that overcome multiple barriers.

When developing place-based sea level rise adaptation strategies, utilities should consider how solutions can be scaled or developed to address their unique adaptation needs while also providing additional benefits, or co-benefits, to their organization, ecosystems, and/or the community at large. For example, a levee to protect a treatment plant could be scaled to also protect nearby assets and neighborhoods, and its design could include civic and environmental amenities like paths, benches, native plantings, and new habitat areas. On an even larger scale, regional coordination is another important component of developing adaptation to sea level rise, as local flood-reduction strategies could increase inundation and its associated damages in other locations within the same bay or estuary (Hummel et al. 2021).

Water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure tends to be large and expensive, with long useful lifespans, so it is common for end-of-century projections to be considered for climate adaptation and resilience strategies. While sea level rise projections might be relatively certain through 2050 (globally they are increasing), the rate and magnitude of that rise is deeply uncertain, with projections diverging significantly after the 2050s. An adaptive risk management approach helps decision-makers address uncertainty and dynamic changes in both natural systems (e.g., how much will sea levels rise and how soon in a particular location) and sociopolitical systems (e.g., regulations, coastal population size, or coastal infrastructure) in order to implement adaptation options that are most effective and flexible over the long term.

The most successful adaptation strategies increase knowledge and collaboration between organizations and communities, which is a key component of advancing sea level rise adaptation. A number of coastal adaptation options are available to decision-makers, ranging from structural (e.g., seawalls and updated design standards) and nature-based (e.g., dunes and wetlands) approaches to policy and regulatory measures (e.g., zoning and floodplain regulations and retreat or relocation). The four common categories of strategies are protect, accommodate, avoid, and retreat. In practice, it is rare for these strategies to be employed in isolation, and usually, a combination of these strategies using physical solutions and policy-based tools is the most prudent way forward. When employing any of these strategies, it is important to develop equitable planning and investment strategies to ensure that sea level rise will not contribute further to the displacement of communities, low-income families, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)-owned businesses. Similarly, the carbon footprint of an adaptation strategy should be considered so it is not maladaptive, thus further exacerbating climate change.

Protection and accommodation strategies facilitate the continued use of the coastal zone by minimizing exposure to and damage from flooding (protection) or accepting higher water levels and occasional flooding by modifying coastal infrastructure and activities (accommodation). The loss of coastal sites to sea level rise is addressed by managed retreat strategies, wherein people and assets are intentionally abandoned or relocated to less vulnerable locations. Avoidance strategies aim to prevent or restrict development in areas vulnerable to sea level rise.

Protecting and Accommodating Water Infrastructure and Supply

In the water sector, protecting and accommodating generally occur through two approaches, usually at different scales:

- Make existing or planned infrastructure (individual assets, systems or facilities) more resilient and/or

- Build a new asset dedicated to addressing the risk posed by sea level rise

Increasing the resilience of existing or planned infrastructure at the asset level usually includes changing policies or updating design standards for new infrastructure and retrofitting existing infrastructure to protect from the impacts of sea level rise. It is often easier to employ these resiliency measures to new assets through a capital planning program while they are being planned and designed. Retrofitting tends to be expensive and challenging because of the scale, location (e.g., subsurface), and interconnected nature of water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure.

Building a new asset dedicated to addressing the impacts of sea level rise (e.g., flooding or water quality issues) could mean building a sea wall or dike, constructing a facility to address water quality concerns (e.g., a desalinization plant), or installing a new pumping system to ensure that sewer and stormwater systems drain properly. This approach is often costly, time intensive, and challenging to coordinate; however, in the long run it may be the more cost-effective and successful solution because it protects existing and future infrastructure and resources. Table 1 provides examples of protect and accommodate approaches and strategies for adaptation to sea level rise.

| Approach | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Protect |

|

| Accommodate |

|

Retreat and Avoidance in the Water Sector

Municipal governments, which are largely responsible for planning in the coastal zone, must balance the demand for development with protecting citizens, preserving cultural resources, and conserving open space and the environment. As sea levels rise and exponentially increase risks along the coast, local governments are increasingly using legal tools to advance avoidance and retreat strategies to adapt to changing conditions. Both retreat and avoidance actions are highly specific to the local geography and community dynamics and require significant coordination between organizations, including political offices, other government agencies, local communities, and utility/services providers. These strategies are often complex, politically charged, and cannot be implemented by the water sector alone. The decision to use these two adaptation approaches falls largely outside of the purview of a water utility; if the community lies in vulnerable coastal areas or new development is approved in those locations, the infrastructure to provide water, wastewater, and stormwater services generally cannot be unilaterally removed, moved, or withheld. This highlights the importance of coordinated holistic adaptation strategy development with input from multiple stakeholders and sectors across the municipality and region.

Several other things make it challenging for the water sector to consider avoidance and retreat adaptation strategies. For example, both approaches require putting physical distance between assets/operations and the source of flooding. Distancing from the coast or river may be impossible—or prohibitively expensive and logistically difficult—for water utilities if they rely on surface water bodies for their operations (e.g., sourcing water from rivers or gravity-fed drainage systems that manage wastewater and stormwater with outfalls along the coast). While a utility may be able to strategically phase out their most vulnerable assets and place new assets in less vulnerable locations, the interconnected nature of water infrastructure often dictates or limits infrastructure placement, which makes accommodation and protection strategies more viable adaptation options, at least in the near term. For example, a pumping station to help move water through a wastewater treatment plant will need to be nearby the plant itself, which may already be in a floodplain where it discharges into a coastal water body. Water utility scope and directive vary widely, but this common reliance on coastal areas makes avoidance and retreat strategies more challenging to adopt when adapting to sea level rise.

Retreating from the coastline or avoiding development in vulnerable coastal areas requires careful consideration of the communities impacted, equity challenges and justice effects, changes to zoning and floodplain regulation, strategic political guidance, and a calculated look at infrastructure networks. Every water utility's relationship with relevant external entities and their internal capacity to address the complex impacts of retreat make this a more difficult set of strategies for water utilities to employ on their own. For this reason, many of the leading practices provided in this guide focus on strategies that protect and accommodate. Yet, there are important examples provided here of communities that are taking steps to retreat and prevent development in vulnerable locations in the first place. Over time, as sea levels rise and the risks increase, these strategies may emerge as the only viable long-term solutions. Table 2 provides examples of avoidance and retreat strategies; note that these strategies are not specific to the water sector and in most cases will be enacted or led by other municipal departments (e.g., the department of planning and development).

| Approach | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Avoid |

|

| Retreat |

|

It is important to note that, in practice, water utilities do not rely on only one set of adaptation strategies but instead build resilience pursuing various pathways simultaneously. The sea level rise adaptation strategies and approaches outlined above are easy to list on paper, but implementing these actions is often hindered by significant challenges and barriers. The next section dives into the specific barriers and leading practices to overcome them.

Barriers to Adaptation in the Water Sector

Sea level rise adaptation may be hindered by any number of factors. Barriers consistently expressed by water sector planners and managers include lack of political urgency, lack of adequate and quantifiable information about potential sea level rise impacts, the long planning timeframe required to address sea level rise juxtaposed with short-term political cycles, lack of direction from state agencies, inflexible permitting and zoning processes, and a lack of funding and other resources to take action.

The barriers to adaptation implementation can be categorized as follows:

The goal of this guide is to provide guidance on how to overcome these barriers and identify opportunities for the advancement of sea level rise adaptation measures.

Expand each section below to see a list of leading practices and view the full page for that barrier as it is outlined in the report. Where applicable, leading practices are followed by real-world examples of that practice from the utilities and communities studied. Some examples include links, tools, and documents that support specific projects, adaptation actions or barriers.

Governance barriers, such as the presence and flexibility (or lack thereof) of regulatory and policy measures, challenges due to political jurisdictions and boundaries, changing priorities due to election cycles. View the full GOVERNANCE page, or select individual practices below.

- Internal staff capacity needs to be a core investment strategy for sea level rise adaptation. Develop guidance, tools, and policies to empower your colleagues and ensure that climate change information is used in the work they do.

- Consider broad social and regional consequences that result from government decisions, policies, and programs and attempt to anticipate unintended and unexpected consequences.

- It is easy to get stuck in analysis paralysis – be prepared to spend as much time, or more, on developing an implementation and funding plan as you did on identifying vulnerabilities and assessing risk.

- Have assessments and action-oriented recommendations ready before the next extreme event and make sure that risks and adaptation projects are included in local hazard mitigation plans.

- Look for innovative ways to coordinate across departments and work with communities, such as a Joint Benefits Authority, to leverage resources, align funds, and aid project coordination.

- Leverage regulatory tools to limit or avoid further development on land that is vulnerable to sea level rise and encourage nature-based solutions with multiple benefits.

- Collaboration across jurisdictions, different levels of government, departments, and stakeholder groups will be required to address the complexity of large coastal protection projects/efforts and bring independent priorities into alignment.

- Consider private-public partnerships as a way to share costs and risk.

- For large-scale coastal protection projects, anticipate implementation challenges such as permitting and long-term maintenance agreements, and work with stakeholders and regulating agencies as early in the process as possible to work towards solutions.

Financial barriers, such as design/construction and maintenance costs of adaptation measures, as well as the availability and flexibility of funding sources. View the full FINANCIAL page, or select individual practices below.

- Develop a funding strategy that includes a menu of funding options.

- Consider the cost of inaction when making the business case for adaptation.

- Conduct cost-benefit and alternative analyses that consider climate change and equity or consider alternative frameworks to guide investments and capital planning.

- Factor maintenance costs of engineered solutions into strategic decision-making.

- Invest in a regional approach rather than individual projects.

- Leverage funds for purchasing land where ownership issues prevent action.

- Develop a dedicated funding source for adaptation and resilience projects.

- Become familiar with funding options available for adaptation and hazard mitigation projects. State and federal governments provide a range of grants and loans that can be used for project scoping or implementation.

Technical barriers, such as limits in the availability of feasible adaptation options (including the capacity to implement the best available options), and the ability of adaptation options to effectively reduce the impacts of sea level rise. View the full TECHNICAL page, or select individual practices below.

- Pay attention to the cumulative effects of climate-related stressors (e.g., sea level rise, precipitation and storm intensity, drought) and interactions with non-climate stressors (e.g., social vulnerability, development pressures).

- Mainstream the iterative nature of adaptation into all decision-making processes and use flexible and adaptive risk management approaches (e.g., dynamic adaptation policy pathways).

- Leverage existing tools where possible to support decision-making. A lack of technical analysis of future conditions should not equate to inaction.

- Unified sea level rise projections for a region, municipality, or city ensure consistency in adaptation planning.

- Nature-based solutions to sea level rise often yield multiple benefits to the community and the environment. Co-benefits not only enhance the community, but can also appeal to funders and create more value for the investment.

- Look for innovative engineered ways to "make room for water."

- Retrofit existing critical infrastructure to accommodate rising water levels.

- While adaptive management approaches are necessary for dealing with the uncertainty associated with climate change, longstanding planning principles and tools (e.g., land use planning or marine spatial planning) can still be useful (or be modified) to better understand risk and identify adaptation solutions.

- Develop standards and tools to help with decision-making and alternatives evaluation.

- Find creative ways to augment staff capacity.

Social or cultural barriers, which may arise from conflicting interests of stakeholders and/or sectors (e.g., public versus private landowners, disproportionate impacts on marginalized groups). View the full SOCIAL/CULTURAL page, or select individual practices below.

- Strategically use visuals that evoke a personal connection to a lived or simulated experience to encourage engagement from community members and those in leadership or decision-making roles.

- Adaptation strategies, projects, or policies that impact residents should be co-produced with community from the outset.

- Find ways to connect sea level rise and flood risk to a variety of audiences of diverse backgrounds. Develop communication tools and create messaging and outreach strategies for a variety of audiences.

- Have patience when building community trust; be prepared for it to take effort and time. Partner with local organizations or faith-based institutions that the community trusts as a way to foster dialog and gain buy-in.

Equity and Environmental Justice

Fully addressing equity and environmental justice impacts and challenges are outside the scope of this guide, but several of the leading practices outlined here provide opportunities to begin addressing these social ills while simultaneously building climate resilience. In fact, the two are inextricably linked; we will not successfully adapt if our most vulnerable populations—including people of color and low-income communities—are not protected and given the tools to thrive.

It is important that water sector practitioners understand the disproportionate impacts marginalized communities face. Marginalized communities – including low-income communities, communities of color, indigenous peoples and tribal nations, and immigrant communities – tend to be disproportionately impacted by climate change more than other populations. While complex and location-specific, this disproportionate impact generally stems from unjust systems that have been in place for many decades (e.g., underinvestment, exposure to pollution and toxins, poverty, limited access to public services, predatory inclusion, discriminatory lending practices, redlining, and outdated infrastructure systems). These entrenched systems are extremely difficult to overturn and require dedicated proactive work.

It is vital that water utilities recognize the structures in place that may result in unequal impacts and actively work to break down these injustices. The water sector and government entities must develop equitable planning and investment strategies to ensure that sea level rise will not contribute further to the displacement of marginalized communities, low-income families, and BIPOC-owned business. Establishing level of service goals/standards and considering how climate change will impact them, is one approach water utilities can use to ensure that services are equally distributed. To reach the standard, investments may need to be concentrated in areas that have historically been excluded from infrastructure upgrades or have deferred maintenance, ensuring that everyone has equal access to the same basic services.

As utilities search for adaptation solutions that build resilience, an equity lens is an essential part of building community resilience and adapting to sea level rise. Water sector practitioners must come to the table ready to partner with and listen to community advocates throughout the entire adaption process. These conversations and partnerships are a necessary first step to begin correcting the egregious wrongdoings of the past.

Equity is a priority in WUCA's Five-Year Strategic Plan. WUCA has committed to "incorporate consideration of equity into all WUCA's work", and is currently engaged in a multi-year partnership with the US Water Alliance to advance water equity and climate resilience so that equity is a priority in the climate adaptation efforts of WUCA and individual member utilities.

Final Remarks

The goal of this document is to identify leading practices to help the water sector move forward and take adaptation action to address sea level rise. While there are many practices presented herein that water utilities can employ on their own—such as raising critical equipment out of the floodplain or making the business case to invest in RO technology—many of the leading practices outlined here require thoughtful coordination with other city departments and stakeholders. In developing this guide and uncovering inspiring examples of implemented adaptation actions from around the country, a fatal flaw in our effort emerged: it is focused on one sector. Piecemeal efforts by one sector may build resilience to a degree, but to successfully adapt in a holistic way, we must start thinking beyond our siloed work environments and coordinate on a scale that has never been seen before.

Another flaw that emerged is the imperfect framing of implementation barriers in four discrete categories; in reality, these barriers are often closely linked and interdependent. For example, a lack of political support may lead to increased financial constraints, and financial constraints might lead to technical limitations. Again, we find that to holistically address sea level rise threats and the broader climate crisis, we need a paradigm shift. While bottom-up efforts can be successful, ultimately, top-down support and a willingness to prioritize planning and projects that address the climate crisis are needed. Therefore, looking at the leading practices to overcome governance barriers may be the best place to start.

While it is clear we need a monumental shift in our thinking about climate change, the small and incremental improvements to improve infrastructure resilience, make staff more prepared, and empower and inform communities do matter—the small changes can sum up to significant impacts. Climate adaptation is an inherently difficult process, and with dedicated effort we can begin pushing past the barriers to create sustainable and equitable water systems and communities. How we begin to accomplish this will vary, but the examples in this guide demonstrate the creative and collaborative steps water utilities nationwide have already taken to achieve this vision.

As utilities undertake adaptation planning and begin the implementation process, we hope the leading practices assembled through this multi-year project provide real-world examples of solutions and success. We would like to conclude by highlighting overarching themes that emerged:

Overarching Themes

- Think big and outside the box. As our climate continues to change, we, as water utilities, must continue pushing the boundaries and strive for innovation. The status quo is not adequate. To truly address the magnitude of the climate crisis, we need to think creatively, beyond traditional solutions.

- Collaborate across siloes with a diverse set of stakeholders. Many of the leading practices highlighted here cannot be implemented by the water sector alone. Strong partnerships with other government agencies, stakeholders, and community members provide a space to include new voices to develop creative, effective, large-scale adaptation projects that address multiple issues and leverage resources.

- Incorporate flexibility and iteration in your adaptation planning and implementation. Adaptation planning to implementation is not a one-and-done process. With ever-changing information and considerable uncertainty, adaptation strategies must remain flexible and be re-evaluated often. The case studies highlighted in this guide often demonstrate where flexibility in the planning process can pay off in the long run by avoiding overinvestments. The ability to pivot as new information and resources become available can serve utilities well throughout the adaptation process.

- Consider all planning and decisions through an equity and environmental justice lens. Flooding hazards and the underlying causes of their disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations pose one of the biggest environmental justice challenges of our time. The climate crisis continues to exacerbate social inequities across our cities and communities, making them inextricably linked. Equitable, co-produced adaptation solutions are vital to ensuring our actions protect—and do not inadvertently harm—the communities we serve. Many of the leading practices in this guide touch upon equity and community engagement, yet it falls short of comprehensively viewing solutions through an equity lens. Going forward, we must shift our thinking to consider water and climate equity in everything we do.

Footnotes

- Water utility or water sector used here generally encompasses the drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater sectors collectively.

- A periodic fluctuation in sea surface temperature and air pressure across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, occurring every 2 to 7 years. (Developed from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

- The ongoing movement of land in response to ice sheet loading and unloading. (Developed from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

- Land reclamation as an adaptation approach to sea level rise is often employed in island nations that have nowhere to "retreat" to or in dense urban coastal cities where the reclaimed land can not only help protect from rising seas but also alleviate crowded conditions. Reclaimed land provides development opportunities, which creates a financial incentive for taking on such a costly, large-scale project.