PLAN

Unfortunately, science will not "solve" climate change in the way we traditionally expect science to solve our challenges. The range of climate projections will stay large and may even grow as more detail and complexity are added to the models used to understand past and future conditions of a naturally chaotic system. As with planning for retirement, practitioners benefit from embracing uncertainty. Faced with unknowns, it is better to move forward with different decision-making techniques and plan for a range of future conditions than spend time and money waiting for the science to become more predictive. Seeking robust, no-regret and low-regret investments that work across a range of future conditions and identifying solutions for future use helps build adaptive capacity within a utility's operations and investments to prepare for whatever the future may bring.

Navigating the planning process in the midst of uncertainty is fundamental to climate adaptation success. The leading practices in the PLAN action area, introduced below, highlight how WUCA members are learning to better assess how changes in underlying conditions impact their systems (e.g., infrastructure, financial, ecosystems, and human resources) and how to plan in a climate change context.

In the PLAN action area, leading practices include:

- Connect with ongoing or upcoming planning processes

- Leverage the power of well-placed climate change screening questions

- Be prepared to be changed by the process

- Learn from earlier climate change planning efforts

- Develop tools that allow information customization

- Take on climate change as another component of risk management

- Leverage existing funding mechanisms (also in SUSTAIN)

- Plan for a range of futures, not a single future

- Employ decision-making science and deep uncertainty concepts

- Build and maintain in-house capacity (also in SUSTAIN)

Connect with ongoing or upcoming planning processes

Climate adaptation can be most effective when worked into ongoing or upcoming planning within a utility, as opposed to creating a separate, standalone document like a climate adaptation plan. Examples of integrating climate adaptation into existing or planned efforts could include:

- Making strategic suggestions when planning documents are revised;

- Adding "consider climate change" to planning checklists;

- Adding language about exploring/evaluating climate adaptations in RFPs and consultant scoping documents; and

- Providing new data sets/analysis by which planning options can be evaluated

Example: A climate change-focused integrated resource plan

Water Forward, Austin Water's integrated water resource plan, which was adopted in 2018, was developed with a focus on addressing climate change impacts, building on regular utility planning such as the state-required five-year water conservation and drought contingency plans. This 100-year plan evaluated future demands in multiple hydrologic scenarios to identify future demand-management and supply strategies to be implemented by the utility and the community. The plan will be updated every five years as part of the utility's ongoing adaptive water resource management approach. Austin Water staff continue to participate in other planning efforts to facilitate strategy implementation, such as development of a City of Austin Climate Equity Plan, green infrastructure plan, watershed master plan, and the state-required Lower Colorado River Basin regional water plan. These planning efforts have provided an opportunity for greater implementation, as described in IMPLEMENT: Be prepared to act when opportunities arise.

Example: Screening questions

Several examples of adding "consider climate change" to planning checklists are included in PLAN: Leverage the power of well-placed climate change screening questions.

Example: Strategic planning

To recognize climate impacts and the need for adaptation more formally, the Portland Water Bureau included several climate adaptation strategies in the utility's updated strategic plan, described in Example: Concrete impacts of warming temperatures.

Example: Enterprise risk management

Southern Nevada Water Authority did an organization-wide risk analysis to understand the breadth of climate risk. See PLAN: Take on climate change as another component of risk management for details.

Leverage the power of well-placed climate change screening questions

One of the first steps to successful climate adaptation is building awareness that future conditions (e.g., weather, sea levels) will be different. While there is often not a clear answer to how big changes will be, a lot can be done by getting decision makers to pause and consider how they might adjust. This could be as basic as inserting climate change screening questions into key planning processes.

Example: Infrastructure screening tool

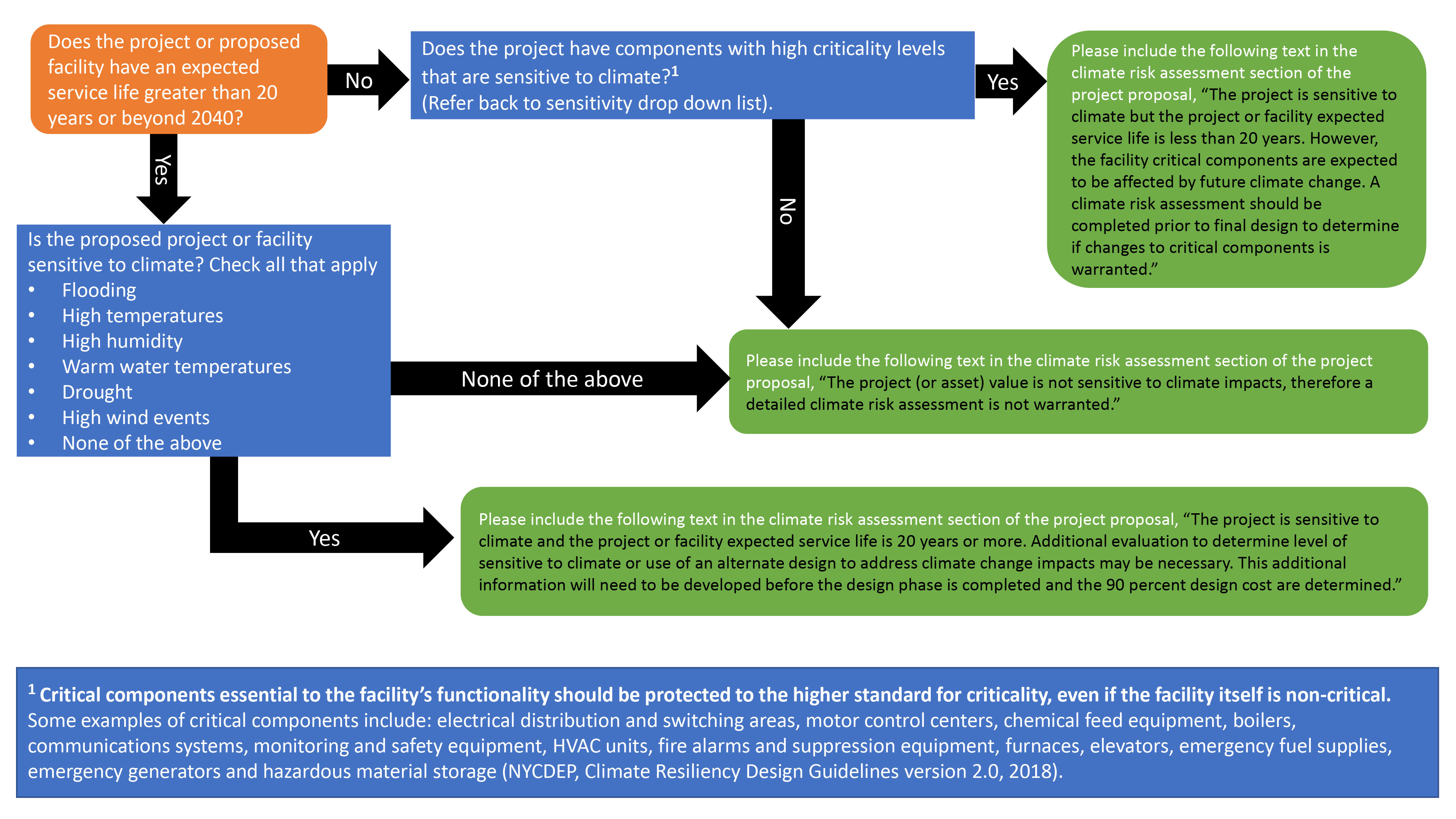

Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) incorporated a screening tool for proposed infrastructure/capital projects to ensure engineers are "considering climate change" in projects that may be climate-sensitive and have a life expectancy beyond 20 years. The screening tool helps the project initiator determine if future climate conditions pose a risk to a project and determine what level of risk assessment would be needed to determine if an alternative design for the project is warranted. The screening tool—a decision tree—is a first step in educating staff in climate-resilient infrastructure (see graphic below). A summary of future climate projections for the service area also helps project initiators adjust their assumptions about future climate conditions. These steps have not required extensive analysis or the involvement of a climate change expert. However, the work has made staff aware that long-lived infrastructure may experience climate different from today, and encouraged them to discuss what should be done differently, if anything.

Decision tree that serves as a screening tool for climate-resilient infrastructure.

SOURCE: SNWA

Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise

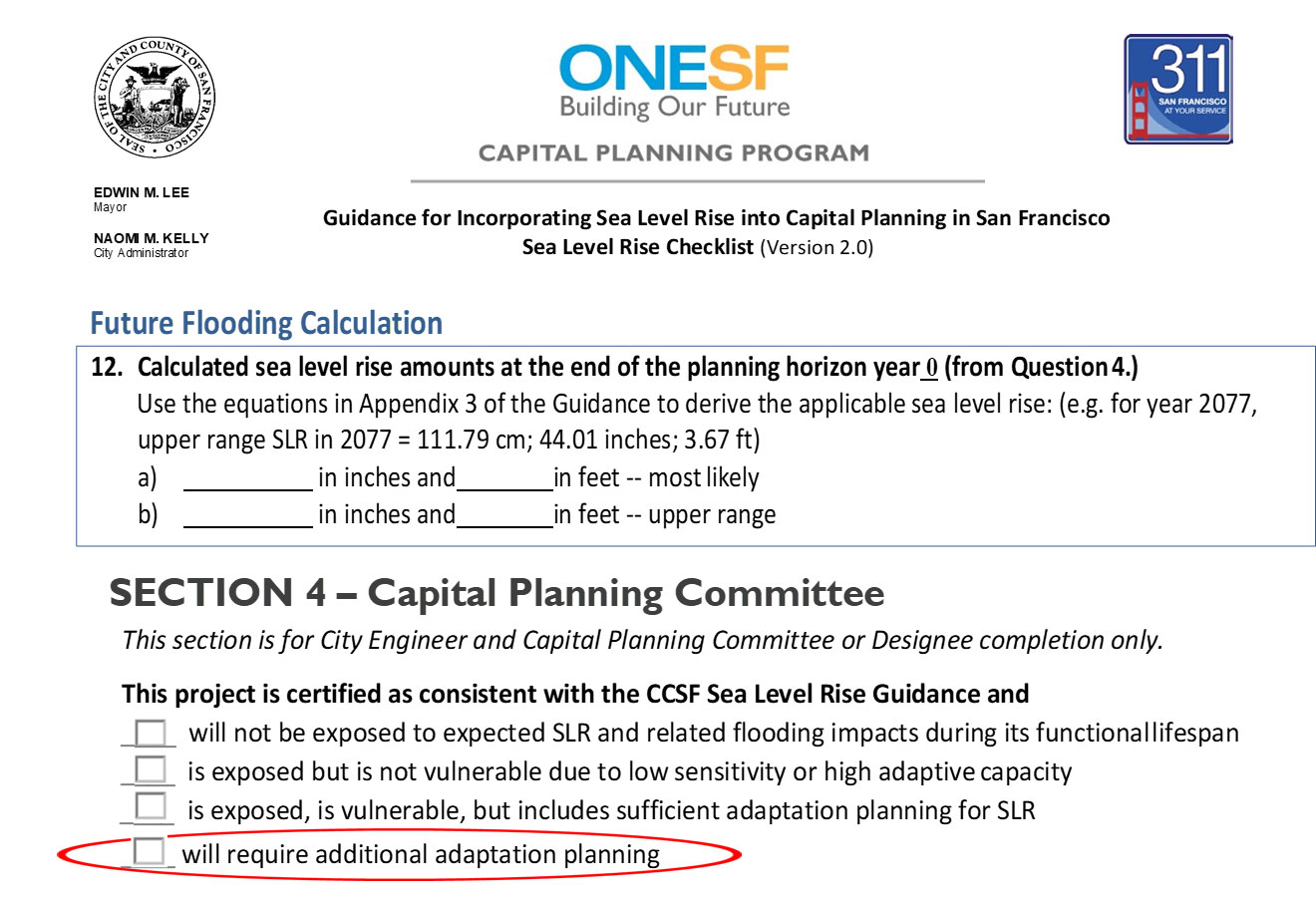

To help City engineers work through anticipated sea level rise (SLR) impacts on future infrastructure, San Francisco adopted "Guidance for Incorporating Sea Level Rise into Capital Planning in San Francisco" in 2014. The Guidance instructs City engineers, planners, and architects managing capital projects to identify their projects' vulnerability to future scenarios throughout their asset's identified life cycle, including vulnerability to water-level elevation caused by an historic 100-year storm surge (which would average 42 inches across the San Francisco Bay shoreline). The Guidance provides consensus median projections identified as the "most likely" level of SLR expected from authoritative documents. The Guidance also presents "unlikely but possible" high end projections based on best available science. These terms were deliberately nonquantitative and intended to be interpreted according to their meaning in plain English. This Guidance, including the checklist in the figure below, has helped promote science-based planning.

Related leading practices on sea level rise

- Example: Sea level rise science in practice under UNDERSTAND: Be a savvy consumer; recognize values and limits of climate science in practice

- Example: Sea level rise projections under PLAN: Plan for a range of futures, not a single future

- Example: Sea level rise science under SUSTAIN: Avoid new climate science whiplash

An excerpt from San Francisco's Guidance, including an influential checklist.

SOURCE: https://onesanfrancisco.org

Additional resources

The New York City Mayor's Office of Recovery and Resiliency has a screening tool. See page 31 for details.

Example: A frame-changing process

Portland Water Bureau's notion of climate adaptation has changed over time. Originally, it was more literal: asking what the climate risks were and conducting analyses to better understand and plan for those risks in order to protect the utility and its mission from them. The Bureau wants to understand what infrastructure changes Portland should make in anticipation of those risks. However, by grappling with uncertainty, learning from peers, and making decisions, the Bureau has come to recognize the larger lesson of adaptation and how to think about planning in the midst of uncertainty. This has been a "frame change" in how the bureau does planning as an organization. Now, instead of thinking of climate adaptation as just "how to plan for a changing climate," PWD broadened its approach to "how do you build resiliency in the face of all things that create uncertainty for the utility going forward?" The Bureau is now engaged in long-term an adaptive planning process to inform decisions around infrastructure investments and projects.

"The challenge of climate is so big, in grappling with it, you can't help but be changed by the process."

- Edward Campbell, Portland Water Bureau

Example: Ten years of climate studies in Florida

A decade ago, Tampa Bay Water (TBW) began investigating climate change by developing its own regional climate model (MM5). It quickly became clear that planning for the strong ocean-land-atmosphere interaction that shapes peninsular Florida's rainfall required collaboration with climate scientists with targeted expertise on Florida's unique climate. This led to the formation of the Florida Water and Climate Alliance (described in UNDERSTAND: Foster sustained relationships with climate science community). When TBW and its research partners discovered that some commonly used statistical downscaling techniques (to localize global and regional climate model output) did not effectively capture Florida's unique climate, they developed a new statistical downscaling technique, called the stochastic analog downscaling method, for the Southeast US. Each applied research effort has built on previous efforts and leveraged tools and techniques developed elsewhere. Having over a decade of consistent, targeted research has helped address key information gaps in understanding Florida's climate.

Florida Water and Climate Alliance has a vast collection of information including scientific publications, workshops, statistical downscaling tools, and data.

Example: WUCA Climate Resilience Training peer-learning

The WUCA Climate Resilience Trainings, described in Example: Learning together, use real-world water utility case studies to share how climate science and planning are tackled in practice. Learning from one another about successes and missteps helps build a stronger foundation for climate resilience in this new and evolving field.

Develop tools that allow information customization

Climate information is rarely ready to use directly. Instead, climate planning requires preparing tools to translate existing information into locally relevant and decision-appropriate knowledge through interpretation, synthesis, and model development. Customizing tools to help others incorporate climate change information can make adoption easier.

Example: Nimble, utility-focused information

Over the last decade, Seattle Public Utilities has worked with outside experts, peers, and its staff to evaluate and evolve approaches to climate-related water modeling and impact assessment. Rather than extensive system modeling using numerous different global climate models, the utility focuses on discerning the right type and reasonable range of global climate models. The utility also, importantly, stays nimble by continuously monitoring and evaluating observed conditions, critical trends, and signpost measures that are not dependent on future projections.

Example: Hydrologic translation

Over the years, Tampa Bay Water has developed water resources/hydrologic decision support tools that allow exploration of dependence between hydrologic variables and climate information. In addition to propagating customized climate projections into these models (described in Example: 10 years of climate change studies in Florida), the tools developed helped the utility customize climate outputs and translate them into more actionable information at locally relevant space and time scales.

- View Tampa Bay Water's Integrated Hydrologic Model documentation, application, and code.

- Floridawca.org has tools and climate data specifically tailored to Florida

"If you don't have a hydrologic model, you don't have jack."

- Alison Adams, former Chief Technical Officer for Tampa Bay Water, highlighting how important hydrologic modeling has been for the utility's planning processes.

Additional resources

Resources that can help quickly uncover your region's climate story include:

See Additional climate service resources for further suggestions.

Developing networks and partnerships with regional utilities, local university and research institutes, and local experts can help in obtaining more locally relevant information, see UNDERSTAND: Foster sustained relationships with the climate science community for more on making and sustaining connections.

Take on climate change as another component of risk management

Infrastructure design and operations have always been carried out under conditions of uncertainty. While climate change adds new elements and challenges, utilities usually have tools already available to help manage uncertainty and leverage risks. Incorporating climate change as a component of an organization’s overall risk management strategy is also useful in mainstreaming climate change actions.

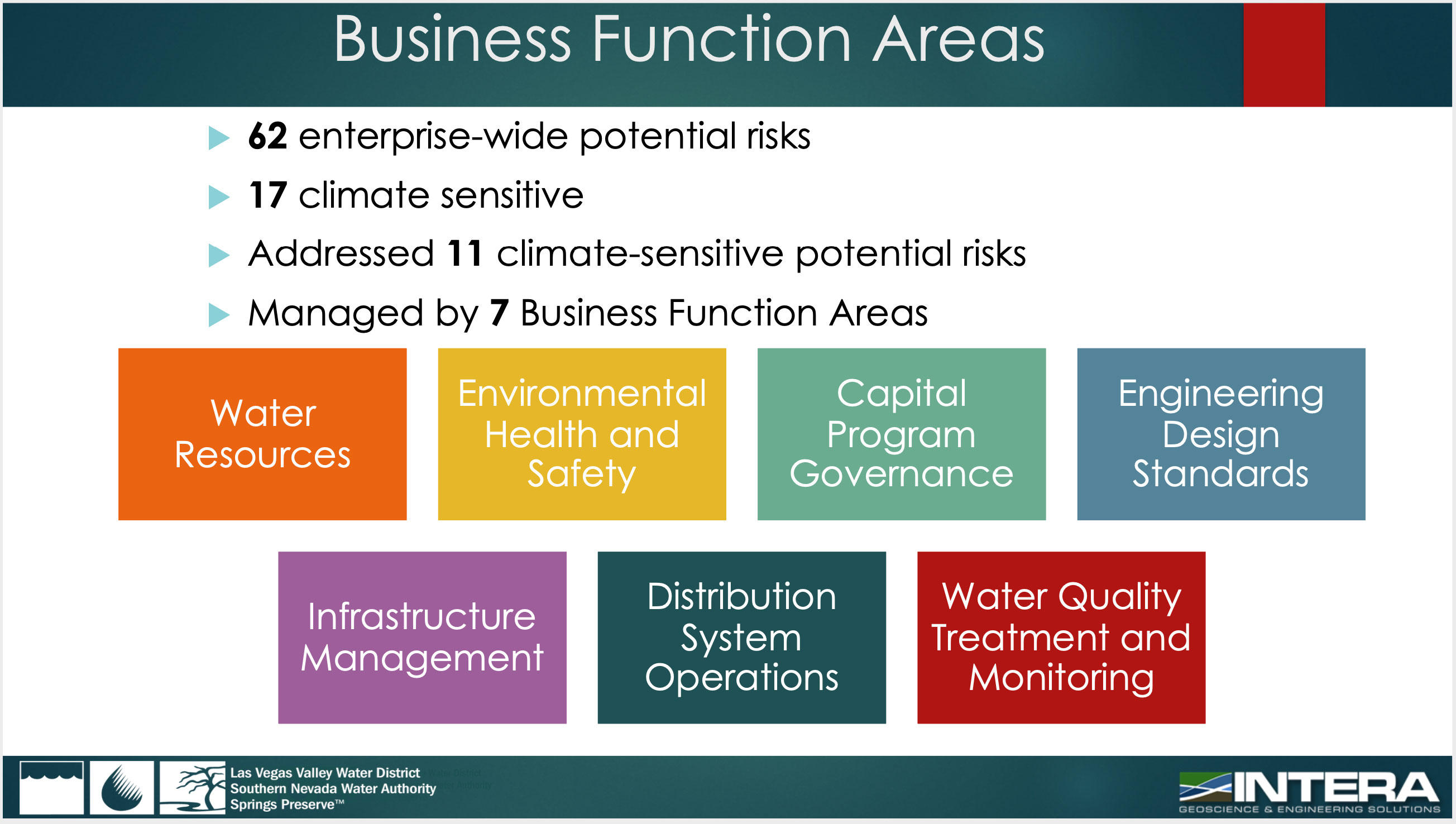

Example: Enterprise risk management

Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) conducted an enterprise risk management (ERM) initiative to document the breadth of future risks the organization could be exposed to, from unplanned increased spending due to asset failure to natural disasters halting water delivery (see slide below). The organization is now completing a secondary assessment to evaluate how the risks identified in the ERM process may be exacerbated by climate change. The climate change assessment (four scenarios are shown below) acknowledges both the department within SNWA currently managing those risks and the actions already in place to manage them, then recommends enhanced actions to account for the increased risk with climate change. One recommended approach, to "consider future climate conditions or scenarios in planning," has the added benefit of mainstreaming climate change considerations across the organization as part of staff's daily work activities to mitigate risks.

A slide from SNWA's Learning From Each Other presentation that highlights the Business Function Areas where risks are already being managed.

SOURCE: SNWA

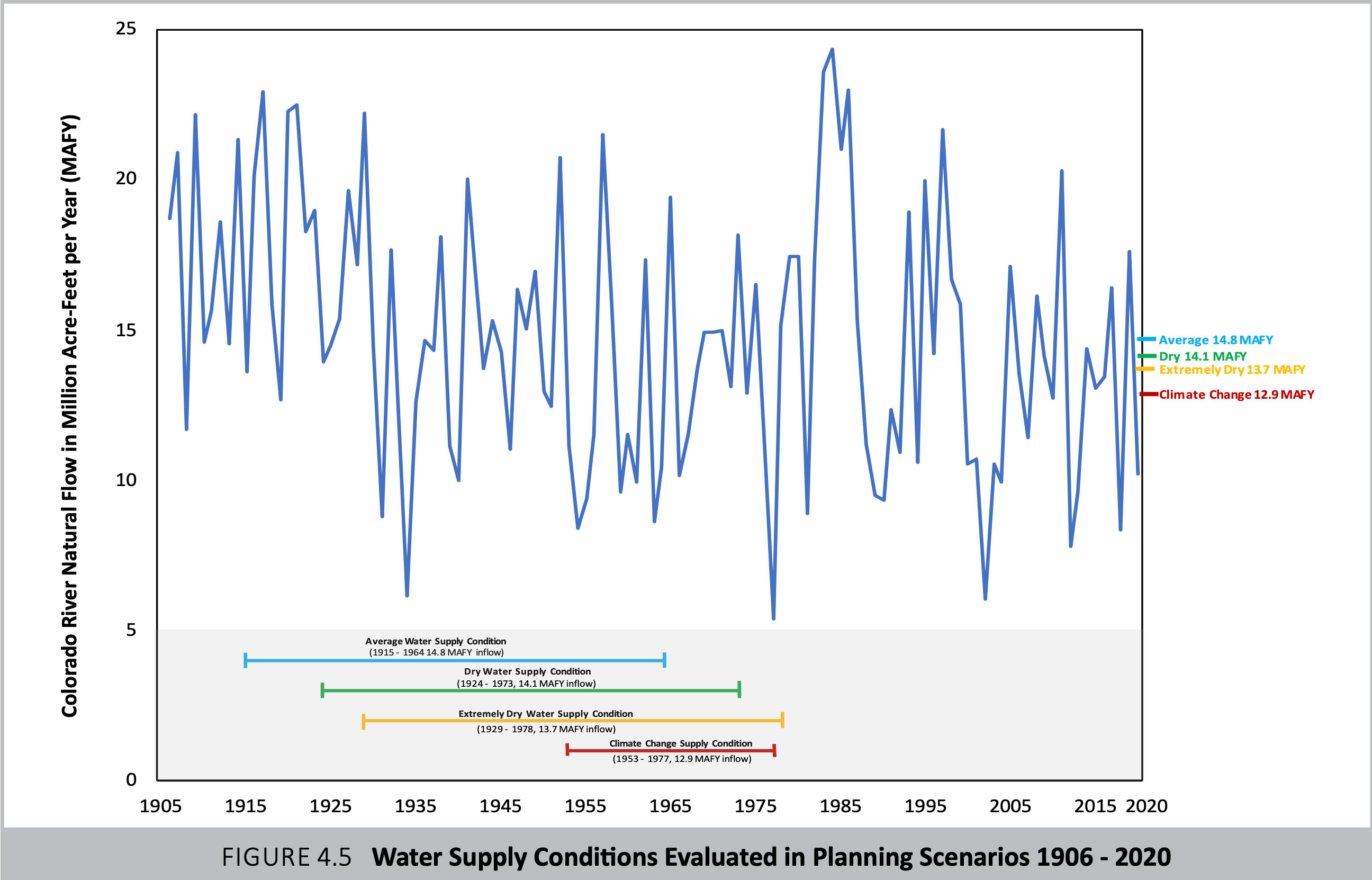

Four supply scenarios SNWA uses in planning.

SOURCE: SNWA 2020 Water Resource Plan

Additional resources

Check out WUCA's June 18, 2019 Learning From Each Other presentation by SNWA for more details.

For more examples of ways utilities are considering risks throughout organizational activities, see SUSTAIN: Approach climate adaptation through mainstreaming.

Leverage existing funding mechanisms

Work to engage, understand, plan, and implement climate change adaptation requires financial resources. Funding is also needed to sustain efforts. State or federal government funding possibilities may exist; they just need to be discovered and leveraged, sometimes creatively.

Examples for this practice can be found in the SUSTAIN section.

Plan for a range of futures, not a single future

While climate change projections indicate clear trends (e.g., increasing temperatures, declining snowpack), specifics will always be uncertain. Planning efforts should focus on understanding a range rather than a single "most likely" future.

See also PLAN: Employ decision-making under deep uncertainty concepts for additional examples.

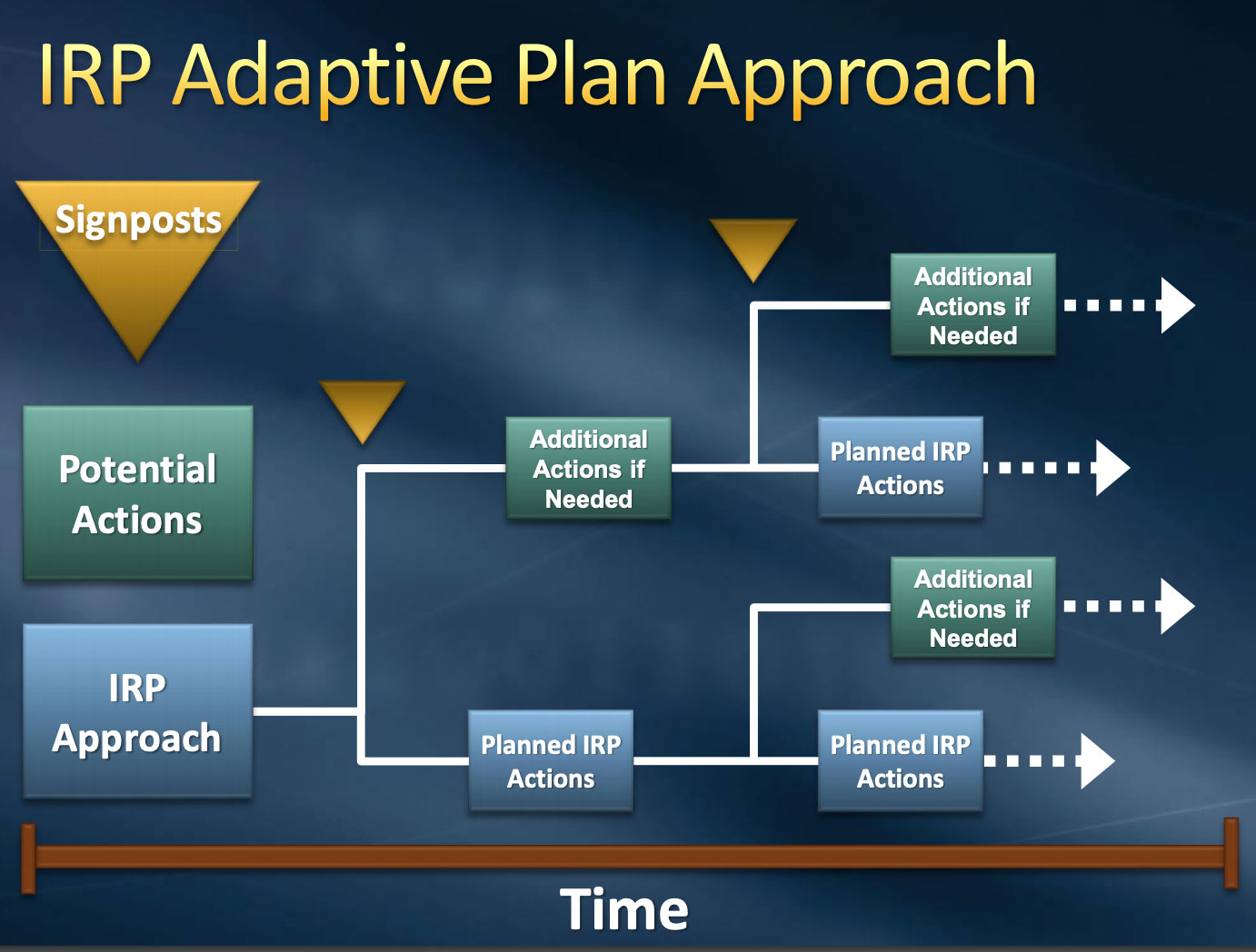

Example: Robust Decision Making

Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (Metropolitan) worked with RAND to conduct a Robust Decision Making analysis of its 2010 and 2015 Integrated Resource Plans (IRPs). The analysis examined how the IRPs perform across a range of plausible climate and demographic futures and identified future scenarios under which the IRPs are vulnerable (i.e., when the IRP doesn’t meet its reliability goals). By identifying these vulnerabilities, Metropolitan can use signposting (monitoring of relevant conditions) to determine when a specific variable (e.g., temperature, demographics) exceeds an identified threshold, then take appropriate management action. Eliminating uncertainty of future projections is unnecessary.

See also PLAN: Employ decision-making under deep uncertainty concepts for additional examples.

More about Robust Decision Making at Metropolitan:

Slide used to explain signposting to WUCA Climate Resilience training in Austin, Texas, December 2019.

SOURCE: Metropolitan

Example: Sea level rise projections

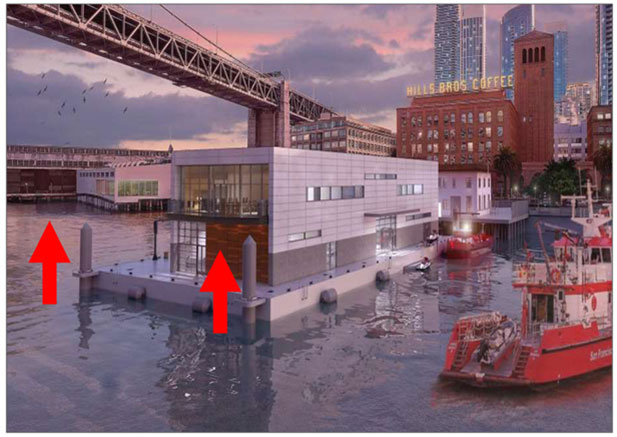

In San Francisco, project managers were given guidance on how to identify an asset’s exposure and sensitivity, then asked to describe its "adaptive capacity" (read more at Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise). Adaptive capacity is an "inherent ability to adjust to sea level rise impacts without the need for significant intervention or modification." This definition encompasses two types of adaptive capacity. First is the ability to add resilience to an existing asset (e.g., a building or boardwalk might be designed to be easily raised in the future to remain out of encroaching waters) or enhance a resilience feature (e.g., a levee might be raised higher). A second type of adaptive capacity is "redundancy" (e.g., an asset's loss due to flooding might not be impactful because other assets provide similar benefits). In both these instances, adaptation to the "most likely" (median) projection would be deemed sufficient in the short term, to be revisited when observations and/or new science more precisely define the SLR trajectory. Where assets do not have adaptive capacity, however, resilience features that provide protection to the "unlikely but possible" (high end) SLR projections should be considered.

One example from this process is the development of floating assets, which can provide uniquely flexible resilience to a variety of SLR scenarios. When San Francisco's aging Pier 22 ½ Fireboat Station #35 reached the end of its functional life and needed to be rebuilt, project managers—in compliance with San Francisco's new SLR Guidance (see Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise)— developed an approach that allows the pier on which the station sits to float upward with the tides and with rising seas. This unique project provides resilience to a range of sea level rise scenarios.

Related leading practices on sea level rise

- Example: Sea level rise science in practice under UNDERSTAND: Be a savvy consumer; recognize values and limits of climate science in practice

- Example: Translating uncertainty and developing guidance for sea level rise under PLAN: Leverage the power of well-placed climate change screening questions

- Example: Sea level rise science under SUSTAIN: Avoid new climate science whiplash

Fireboat Pier Design: Rising with Rising Seas

SOURCE: San Francisco Public Utility Commission

Example: Adaptive management approach

Climate scientists project that increases in temperature and changing precipitation in central Texas will likely lead to longer and more severe droughts broken by more intense precipitation events. In developing Water Forward, an integrated water resource plan, Austin Water evaluated multiple future hydrologic scenarios developed through climate and stochastic modeling to ensure reliability of the plan recommendations through a range of possible futures. The plan aims to improve water supply resiliency during droughts worse than those experienced in the past and other significant events, including floods with water quality upsets. The utility is implementing the plan through an adaptive management approach, allowing Austin Water to adjust in response to changing conditions. This work is described further in PLAN: Connect with ongoing planning processes.

Example: Demand forecast scenarios

The San Diego County Water Authority's (SDCWA) long-term planning process includes an assessment of supply reliability using a traditional scenario planning approach. This process evaluates multiple factors that may potentially impact the region’s supplies – including a qualitative analysis of potential climate change impacts. The SDCWA’s 2015 Urban Water Management Plan contains the assessment of the region’s future resource mix and addresses potential supply uncertainties. Through a scenario planning approach, a potential "supply gap" was calculated due to some (or all) of these uncertainties, and potential adaptive management strategies for the next 25 years were identified.

The plan also includes demand forecast scenarios based on climate modeling results. The climate change projections are run through the SDCWA's econometric water demand model to generate a local consumptive use forecast for comparative purposes.

Additional resources

Increasingly more information is available on how to effectively plan for an uncertain future. See Additional planning amid uncertainty resources for more details.

Employ decision-making science and deep uncertainty concepts

Decision-making science provides tools to help navigate and plan for multiple futures that include climate change alongside other unknown and surprising future changes. Making decisions in the midst of uncertainty is not new, but climate change adds an additional layer of complexity. A diversity of climate change assessment approaches incorporates this new deep uncertainty to allow utilities to make robust decisions and avoid being paralyzed by the unknown.

See also PLAN: Plan for a range of futures, not a single future for additional examples.

Example: Scenario planning

Denver Water adopted scenario planning in 2008 as a simple and systematic way to plan for a range of plausible, equally likely future scenarios. Scenario planning is easy to understand in concept and allows for broad engagement, leading to widespread buy-in throughout an organization. Denver Water seeks to build a system that is robust, flexible, and diverse, with assets that are scalable and spread evenly throughout its collection and distribution systems.

The Portland Water Bureau also adopted a scenario and adaptive planning approach in its Supply System Master Plan, which has served the utility in more ways than traditional planning. Learn more at SUSTAIN: Value climate adaptation as more than a plan.

Scenario planning resources are available from WUCA, RAND Corporation, and even National Park Service, which provide examples of how to conduct a simplified scenario planning process; see additional planning amid uncertainty resources below.

Example: Planning amid uncertainty training

Valuable lessons on how to plan amid uncertainty are provided by WUCA's Building Resilience to a Changing Climate training, described in Example: Learning together. The training provides an overview of planning methods for addressing uncertainty when incorporating climate science into utility decision-making processes. View slides on Scenario Planning.

Additional planning amid uncertainty resources

WUCA developed two white papers to help practitioners embrace climate uncertainty, make progress on climate adaptation, and change their planning approaches:

- An overview of different planning approaches to prepare for a changing climate (and other conditions), entitled, "Decision Support Planning Methods: Incorporating Climate Change Uncertainties into Water Utility Planning"

- A series of detailed case studies illustrating utilities moving forward in the context of uncertainty, "Embracing Uncertainty: A Case Study Examination of how Climate Change is Shifting Water Utility Planning"

Information is increasingly available on how to effectively plan for an uncertain future. WUCA utility members have found these resources useful:

- The Society for Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty

- Leading research institutions on decision science include Cornell, University of Colorado, University of Massachusetts Amherst, RAND, Deltares, University of Cincinnati, etc.

- AGWA Adaptation Pathways guide

- Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice (Vincent et al., 2018):

- See chapter on Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways by Haasnoot, Warren & Kwakkel (pp. 71–92)

- Useful website from CoastAdapt

- Judy Lawrence presentation on Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning

- The Center for Adaptation Science and Solutions led a 10-month Colorado River Conversations Scenario Planning process to explore extreme events

Build and maintain in-house capacity

Climate adaptation work can be done both within and outside of an organization, though action ultimately requires work within. It can be a significant undertaking, requiring hiring or redirecting staff time. It is better to not assume people can incorporate climate adaptation work into their existing responsibilities.

This practice is included under both PLAN and SUSTAIN climate adaptation actions.)

Example: Hiring a climate program manager

Climate adaptation is a long-term process. Utilities can experience long-term benefits by building organizational capacity to do this work rather than relying on external consultants or outsourcing. The Portland Water Bureau (PWB) has been planning for climate change since the 1990s but scaled up its internal investment in climate impacts analysis in 2012 by hiring a climate change staff person. The climate change position evolved from a part-time role to a full-time Climate Program Manager over the years, as more mainstreaming opportunities were identified. The position has enabled the utility to work on multiple climate adaptation projects and engage with WUCA without having to reduce resources in other program areas.

Other WUCA members have also hired climate program managers; see Example: A dedicated person to support champions utility-wide to learn more.

The Portland Water Bureau is embarking on further adaptive capacity building in its five-year Strategic Plan which highlights strategies to integrate climate adaptation work into multiple parts of the organization.

Example: An in-house hydrology model

The Portland Water Bureau (PWB) developed internal modeling capacity for climate adaptation through the WUCA Piloting Utility Modeling Applications (PUMA) project (2012–2014). During this project, the utility asked scientists to train staff in the use of a newly developed hydrologic watershed model and downscaled climate data. The ultimate goal was for utility staff to lead future efforts to use these tools, since they are most familiar with system planning and needs. Following the PUMA project, the utility hired a full-time Water Resource Modeler in 2015 to operate and manage the modeling tools that were brought in-house. The modeler position adds value to water supply analysis, demand modeling, water quality modeling, and other efforts where climate and hydrologic data are used systematically for planning purposes. By hiring staff to focus on modeling and climate change, PWB substantially increased its institutional knowledge and technical capacity over time.

WUCA's "Actionable Science in Practice" (2014) report describes the PUMA project process and the importance of building in-house capacity for several utilities, including the Portland Water Bureau.

Portland Water Bureau climate change research meeting with external partners

SOURCE: PWB

Additional resources

Hiring or redirecting staff to have climate change resilience as all or part of their job description is ideal. However, there are ways to build awareness within your utility through a collective effort (see SUSTAIN: Establish a community of practice to integrate climate change utility-wide for examples). It is also noteworthy that a position might develop over time, as Portland Water Bureau’s example of hire a climate program manager (above) describes.